Hidden Wonders | A Village with Japan's Lowest Population Density

人口が少ない地域と聞くと、不便さや将来への不安を思い浮かべる人もいるかもしれません。けれども、福島県の檜枝岐村のように「日本で最も人口密度が低い」とされる場所には、その数字だけでは語れない暮らしのかたちがあります。人が少ないという事実は、本当に弱さなのでしょうか。それとも、別の価値を生み出す可能性を秘めているのでしょうか。あなたなら、どんな点に意味を見いだしますか。

1.Article

Directions: Read the following article aloud.

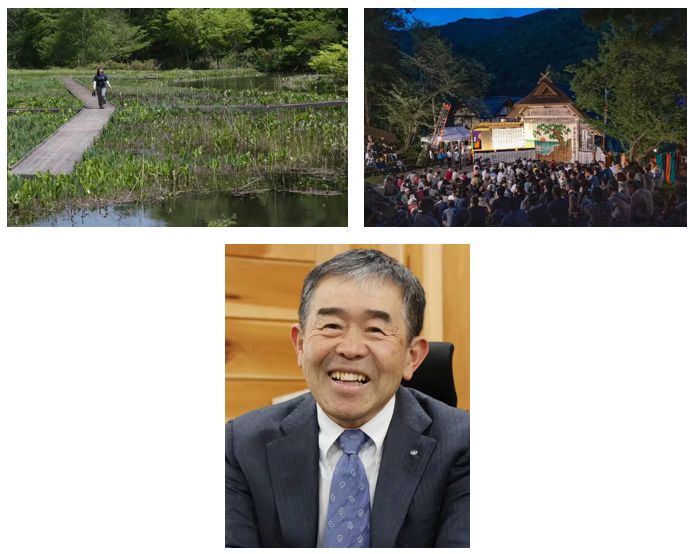

Hinoemata Village covers about 390 sq km (150 sq mi) and had a population of 479 as of the end of March 2025. This translates to a population density of just 1.23 people per sq km (3.2 per sq mi), with an aging rate of 39.87%.

By comparison, Tokyo's 23 wards span about 628 sq km (243 sq mi), roughly 1.6 times the size of Hinoemata. Yet they are home to around 9.87 million people as of March 1, 2025, with a population density exceeding 15,700 per sq km (40,700 per sq mi).

The main settlement, where the village office is located, sits at an elevation of around 1,000 m (3,280 ft), and winter snowfall can reach as much as 3 m (10 ft).

While the village has a few agricultural cooperative shops, the nearest convenience stores and large supermarkets are in neighboring Minamiaizu Town, about one hour away by car. The village's only clinic provides internal medicine and pediatric services, so residents must travel to Minamiaizu Town for hospital-level care.

Hinoemata has one combined elementary and junior high school, with 46 students from first grade through the third year of junior high in the 2025 school year. Most high school students attend schools in Minamiaizu Town or Aizuwakamatsu City, more than two hours away by car. To support students who must live away from home, the village operates a dormitory in Aizu-Wakamatsu called Oze Dormitory.

Surnames in the village are also distinctive. Three names, Hoshi, Hirano, and Tachibana, account for about 70% of the population. Of these, roughly 60% are Hoshi, 30% Hirano, and 10% Tachibana. Mayor Nobuyuki Hirano says, "People usually call each other by their first names, and if two residents share the same full name, we add the name of their district to tell them apart."

To outsiders, life in the village may seem full of inconveniences, but many residents see it differently. Mitsuru Hoshi of the village office's General Affairs Division recalls with a smile, "It was fun living at Oze Dormitory when I left home for high school, because I was always with my friends and away from my parents." He adds that spending those years outside the village with friends only strengthened their bonds.

When Typhoon Hagibis struck eastern Japan in October 2019, river embankments collapsed, causing a village-wide power outage and damaging roads. More than 50 people, including Mitsuru's family, took shelter in public halls. Mitsuru himself was unable to leave work. "I was worried about my family, but people helped set up partition tents at the shelter," he recalls. "In an emergency, it is reassuring when everyone knows each other."

Toshihide Hoshi, head of the village Chamber of Commerce and owner of a local inn, says, "The village itself is like one big company. When I came back after working elsewhere, I truly felt how strong our social ties are." He adds with a smile, "Out of the 15 or 16 classmates I had, 10 are still here, and we have a great time."

About 98% of the village is forest, and the inhabited area covers only around 2 sq km (0.8 sq mi). Daily life is compact and easy to manage on foot, and there is no school bus service. Mayor Hirano says the village is like a "compact city," emphasizing its convenience.

Still, population decline and rapid aging remain serious challenges. Mayor Hirano admits, "Honestly, it is difficult to increase the population," but notes that Japan has entered an era in which many older people continue to work. "We want to create a system where they can contribute as part of the workforce." He believes that being needed can give people a sense of purpose.

The village's close-knit culture can be an advantage. Everyone interviewed in Hinoemata said that kodokushi, the phenomenon of dying alone and remaining undiscovered for a long time, does not occur there.

本教材は、一般社団法人ジャパンフォワード推進機構、株式会社産経デジタルより許諾を得て、産経ヒューマンラーニング株式会社が編集しています。

テキストの無断転載・無断使用を固く禁じます 。